WANTED: A Super Bad Dawg Story

Published 1:30 pm Sunday, July 18, 2021

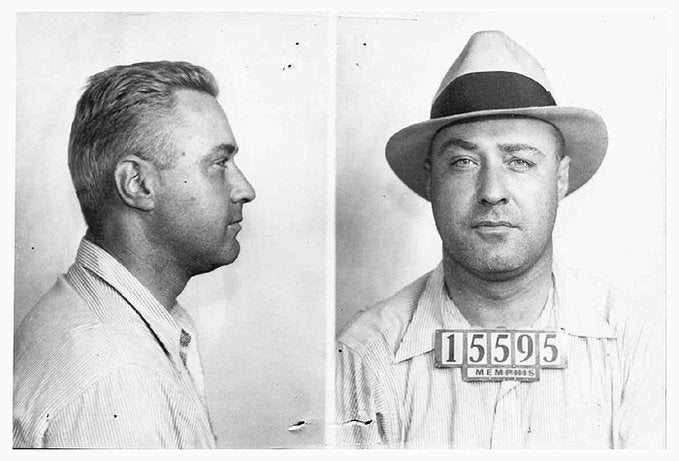

Bank robberies, kidnappings and FBI showdowns pepper ’30s gangster Machine Gun Kelly’s mythology; however, the man who became the notorious criminal began as a student at Mississippi State University.

The man now known as Machine Gun Kelly was born George Kelly Barnes to George and Elizabeth Barnes in 1895. He grew up in Memphis, Tenn., and did not earn a high school diploma. In the summer of 1917, his mother wrote to Mississippi A&M College to learn of the requirements that would allow Kelly to attend the university.

The president at the time, William Hall Smith, replied to her letter. His letter, which can be found in the MSU archives, included the information requested and said, “We will endeavor to serve his best interest.”

“Maroon and white: Mississippi State University, 1878-2003,” university archivist Michael Ballard’s book chronicling the history of MSU, states that because Kelly was a student admitted under special circumstances, he could not become an official student until he had proved himself academically.

According to Kelly’s transcript for the university, which can also be found in the university archives, he attended Mississippi A&M for 1.5 semesters from 1917-1918. During his time at the university, he earned one C-plus in physical hygiene, many Cs and Ds, a zero in woodwork and an incomplete in military science. He had 31 demerits first semester and managed to earn 24 demerits in the early weeks of second semester.

In an article from the Jackson Daily Newspublished in 1953 headlined “Head of State’s Drawing Department Ends 50 Years of Service At College” found in the university archives, Matthew Livingston Freeman, a retired MSU professor of drawing, said he remembered Kelly as a student. Freeman said Kelly climbed the flagpole to repair the pulley at the top to “wash out” his demerits.

While at the university, Kelly met his first wife, Geneva Ramsey. According to the book “Public Enemies: America’s Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933-34” by Bryan Burrough, when Kelly dropped out of Mississippi A&M, his father disowned him. Soon after, Kelly eloped with Geneva and began working for his father-in-law’s construction company. During this time, he had two children with Geneva.

After his father-in-law died in an accident, Kelly began bootlegging — illegally transporting alcoholic substances — and was arrested in 1924, causing his wife to leave him.

According to “The Encyclopedia of American Crime,” a copy of which is found in the MSU library archives, Kelly never fired a shot at anyone and never killed anyone.

A criminal profiler was quoted as saying Kelly was “a good-natured slub, a bootlegger who spilled more than he delivered.”

Kelly met Kathryn Shannon, his second wife, in Oklahoma City while attempting to make it once again as a bootlegger. Kathryn was involved in the criminal underworld because her mother and step-father ran a “fugitive farm” in Texas where people in trouble with the law could pay to hide out at the Shannons’ ranch. The couple married in 1929.

Kathryn is credited with giving Kelly his reputation and even bought him his trademarked machine gun. She had Kelly shoot walnuts off fence posts for target practice. Kathryn also handed out empty cartridge cases to other criminals and would claim he was away robbing banks.

“Have a souvenir from my husband, Machine Gun Kelly,” she was reported to say.

Kelly managed to become part of a few bank hold-up gangs in Texas and Mississippi from 1931 to 1933, and the plans went smoothly.

An article found in the university archives, originally published in The Clarion-Ledger, titled “Jacksonians Got Involved In Biggest Bank Robbery,” said Machine Gun Kelly robbed Tupelo Citizens’ State Bank in 1934 with four other men. The gang stole $38,000 in cash, $15,000 in negotiable bond and over $10,000 in traveler’s checks.

Homer Edgeworth, the teller who was forced at gunpoint by Machine Gun Kelly to help empty the bank, said the experience was harrowing. Edgeworth said the robbery only took 10 minutes because the bank had been compromised so the thieves knew the layout.

Kelly said the first person to stick his or her head outside would be shot.

“They meant it too,” Edgeworth told The Clarion-Ledger. “We were lucky nobody started anything with them. For that heavily armed bunch of thugs could have killed out half the town.”

Once they left, Edgeworth called the police. Kelly was expected to head for Memphis; so police set-up roadblocks in that direction, however, he went the opposite way and escaped.

According to “The Encyclopedia of American Crime,” Kathryn persuaded Kelly to “go big-time” like other gangster and plan kidnappings. With a man named Albert Bates, the Kellys formed a kidnapping gang.

It targeted Charles Urschel, a millionaire oil tycoon from Oklahoma City and broke into the Urschel home on July 22, 1933. The Urschels were playing bridge with their friends the Jarretts. Kelly and Bates held the foursome at gunpoint and took both men when no one would identify Urschel; later, they dumped Walter Jarrett on the side of a road after identifying the two men.

The FBI report on the kidnapping of Charles F. Urshel, which can be found in the MSU library archives, said the kidnappers demanded $200,000 ransom.

The ransom note read, “If there should be any attempt at any double XX it will be he [Urschel] that suffers the consequences.”

A note arrived giving further instructions several days later. E.E. Kirkpatrick, a friend to Urschel, received these letters and eventually exchanged the ransom money for Urschel’s return.

According to “The Encyclopedia of American Crime,”once the kidnap gang had the ransom, Kathryn wanted to cover its tracks by killing Urschel. However, her husband talked her down by saying, “It would be bad for future business.”

Urschel was returned home on July 31.

The FBI managed to track down the criminals because of Urschel’s memory. He was able to recall specific details about the place where he was held that helped identify Kathryn’s parents’ ranch in Texas. The Shannons and Bates were taken into custody.

In the book “Bloodletters and Badmen,” an excerpt of which can be found at the university archives, states Kelly was furious after his in-laws were arrested. He wrote threatening letters to his former victim and Joseph Keeyan, who was in charge of prosecution at Oklahoma City where the Shannons’ trial was being held.

“If the Shannons are convicted look out, and God help you for He is the only one that will be able to do you any good,” Kelly wrote in a letter to Urschel. “Now, sap — it’s up to you, if the Shannons are convicted you can get you another rich wife in Hell because that will be the only place you can use one.”

Soon after, the Kellys were found in Memphis by Detective Sgt. W.J. Raney and two other officers. After the three broke into the bedroom, Raney shoved his shotgun into Kelly’s stomach.

“I’ve been waiting for you all night,” Kelly replied.

The Kellys were arrested and blamed each other during the trial. On Oct. 12, 1933, the Kellys were sentenced to life imprisonment. Bates and the Shannons also received life sentences.

Kelly wrote to Urschel in prison before he died of a heart attack at the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kan. on July 17, 1954.

“These five words seem written in fire on the walls of my cell,” Kelly wrote to Urschel. “Nothing can be worth this.”